|

The

fans of hand fans who give me the pleasure - and the honor - of

following me on this site or in my various articles or lectures know

that we like to "read" the stories we see (or sometimes that we think

we see!) on fans. As in other works or objects of art, they are often

linked, as we know, to ancient Greco-Roman history or to religious

history as presented in the Bible. As knowledge of these stories is

less and less a part of mainstream secondary education, it is important

that anyone wishing to open an art book, visit a museum ... or look at

a fan try to learn a little in these fields: there are in most

languages (spoken in Europe or the Americas) excellent and

easy-to-access books.

Besides understanding those historical scenes (or at the same time!),

it is necessary to know how to make an allegorical reading of paintings

or prints and therefore of the fans which are often inspired by them.

There too, one finds books allowing to understand many of these

allegories. The most famous, and the easiest to find, is the Iconologia

by Cesare Ripa (1555-1622), first published in 1593 but whith countless

later editions and translations, which has inspired European artists

for centuries..

One will easily find on the fans the most common allegorical figures,

such as Virtues, Seasons, Fame, Justice...

Let us content ourselves here with showing Virtues and Seasons on fans from the 1780s.

At first, Virtues: we can easily recognize on the left Faith carrying the Cross and a (sacred) book; in the center, Charity, which loves and nourishes her children, and on the right, Hope, whose anchor is the traditional attribute.

As for Seasons, simple logic

(although the ongoing climatic upheavals may contradict it!) makes easy

to see, from left to right on the fan from which we extract them, Autumn, Spring, Summer and Winter. Why this change in the natural course of time? We don't know! Note that seasons often appear in the form of their associated deities: Bacchus for Autumn, Flora or Venus for Spring, Ceres for Summer and Boreas or Vulcan for Winter.

All ancient fans amateurs also

know the importance on fans of various symbols, in particular those

related to Love: doves, torches, arrows and quivers, and of course

cages and more or less flying birds, symbols of a... more or less lost virginity.

Besides

those easy to understand allegories, it is in almost all European

painting (and therefore on fans) from the 16th to the 18th century that

we must look for allegories. Of course, they sometimes end up becoming

a process that has lost the original message, before being sometimes

copied in the 19th century in a mechanical and decorative way, without

any message to convey. But it must be understood that for the 'noble'

history painters at the time of Louis XIV there was hardly a painting

that could not compose a real discourse. This discourse was sometimes

composed by the commissioner: so many religious paintings, made for a

church, a community, a specific brotherhood, and integrated into an

overall decoration (unfortunately often disappeared due to fires,

looting, refusal of images by Protestantism, vandalism of the French

Revolution ... and sometimes even overzealous post-Vatican II Concile

Catholic priests!). So the indications of the sponsors or the

explanations of the artists have often disappeared. They had perhaps

been essentially verbal, though.

It therefore seems interesting to give here an illustration entirely

commented on by its author, the great painter Charles Le Brun, first

painter to King Louis XIV. The latter had asked Isaac de Bensérade

(1612-1691), one of his favorite poets, co-author of many of the ballets so appreciated by the king, to transcribe into poems, for the instruction of the Dauphin, Ovid's Metamorphoses.

This sumptuous work, illustrated by François Chauveau (one of the best

engravers of the time) assisted by Sébastien Le Clerc and Jean

Lepautre, was published in 1676. Despite the extreme quality of the

engravings -still quite useful for the old fans amateur wanting

to identify a mythological scene!- and of the printing of the texts, it

was not a success: the type of poems chosen was no longer in fashion.

They are 13-line cross-rhyming poems, to which a verse of half of the

first line is added in the middle and at the end. In my opinion, the

work of Bensérade would have deserved a better reception, because it

sums up very well a number of fables, and not without wit. But we do

not study here these poems, nor the remarkable engravings which

illustrate them, although they are full of allegories, as you may guess.

What we are looking at now is the frontispiece of the book, which we show below.

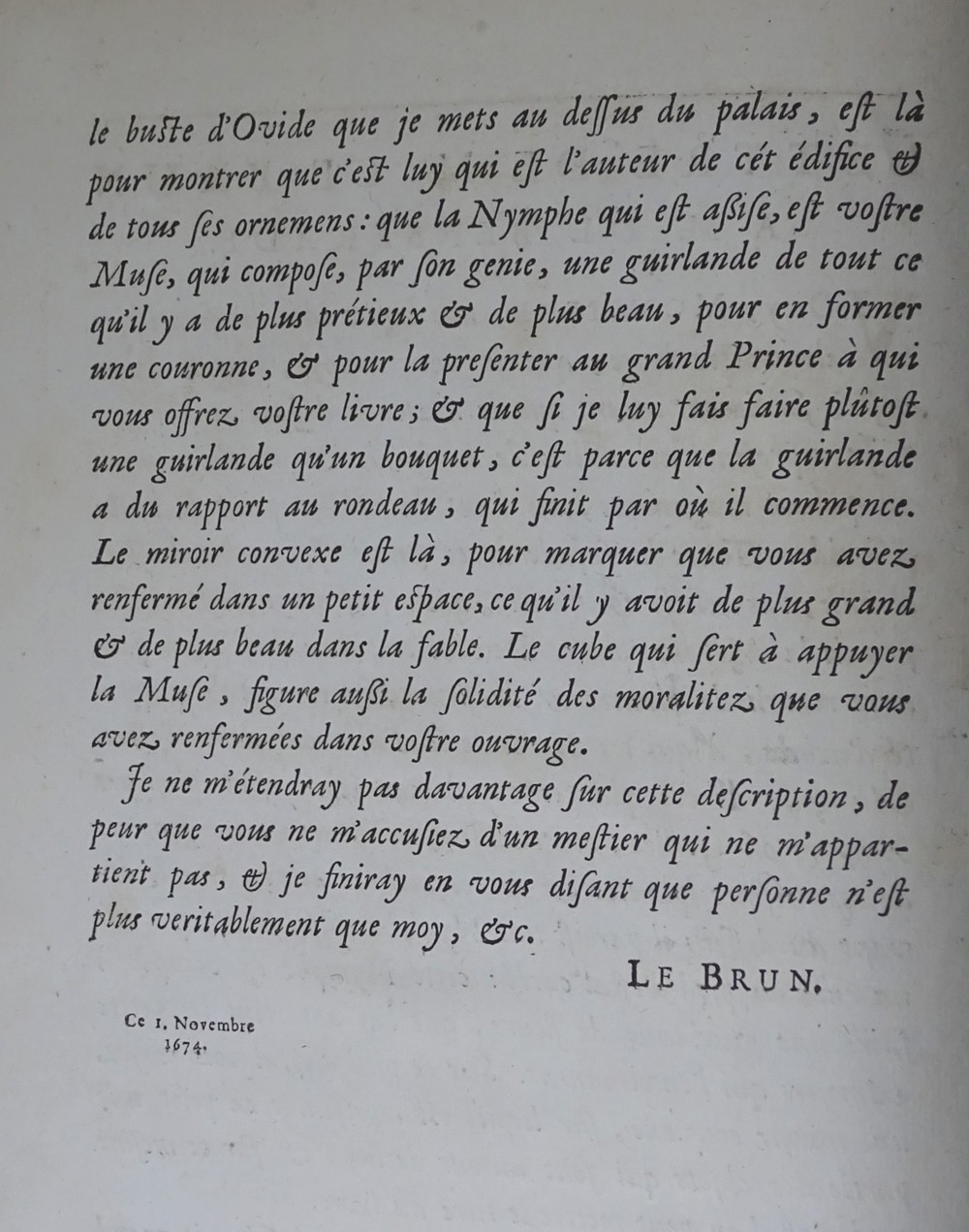

Generally, on seeing this type of illustration we must try to guess the intentions of the artist. But what was (perhaps!) understandable to the educated public in 1676 is generally no longer so. Here, we are fortunate that Charles Le Brun explained in detail his design (and therefore his drawing, the same word 'dessein' in XVIIth century French-) in a letter to Isaac de Bensérade, which this one inserted at the head of the book. Here is this letter:

To

make it easier for you to read both the text and the allegory, I

reproduce it below with Charles Le Brun's text in English. Translation

and subsequent mistakes are mine!

|

M. Le Brun's letter to M. de Benserade

Find

here, Sir, a slight idea of the frontispiece of your book that I am

sending you to get your opinion before finishing this drawing.

I represent in the middle of the sheet and in the distance a magnificent palace, on top of which I paint Ovid's bust. The entire facade of this palace is enriched with paintings, bas-reliefs and statues, which represent several subjects of the Metamorphoses. In

front of this palace, there is a parterre filled with plants and

flowers, and surrounded by a number of trees to which the heroes of the

Fable have given life. Around

these plants and these trees are several Cherubs or Genies, who pick

the flowers and the gums of these same plants and these same trees. On

the front of the drawing we see a nymph sitting and leaning on a cube

or square pedestal: this Nymph is busy making a garland of flowers,

brought to her by the little cherubs who surround her. On this pedestal you see a convex mirror on which is represented in small a part of the objects which are around it. On this same pedestal we can put the title of the book.

I do not believe, Sir, that this drawing is in great need of explanation. Because

I think you understand that the bust of Ovid that I put above the

palace is there to show that he is the author of this building and all

its ornaments;

that

the sitting Nymph is your Muse, who composes by her genius a

garland of all that is most beautiful and precious, to form a crown and

to present it to the great prince to whom you offer your book; and that if I make her composing a garland rather than a bouquet, it's because the garland has a relation to the rondeau, which ends with where it begins.

The convex mirror is there to show that you have enclosed in a small space what was greatest and most beautiful in the fable.

The cube which serves to support the muse also represents the solidity of the moralities which you have contained in your work.

I

will not continue this description any further, lest you accuse me of a

job that does not belong to me, and I will end by telling you that no

one is more truly yours than me etc.

Le Brun

Ce 1er novembre 1674.

|

We will easily find on our fans characters very similar to those represented by Charles Le Brun on illustrating these Metamorphoses d'Ovide en Rondeaux by Bensérade. Should they be given exactly the same meaning? Probably not! But everyone will enjoy, I'm sure, looking for the meaning of the images on their fan leaves, and "reading them"!

|